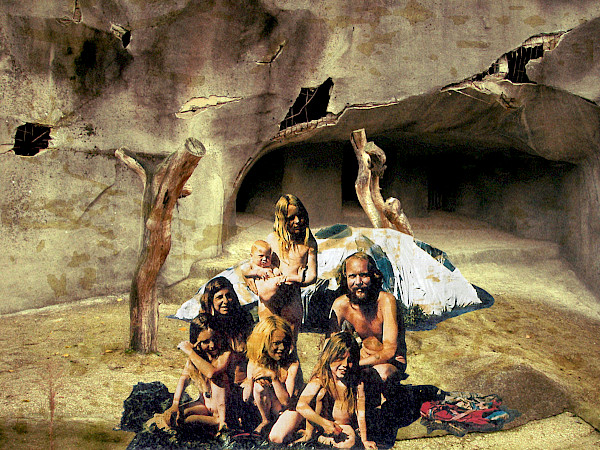

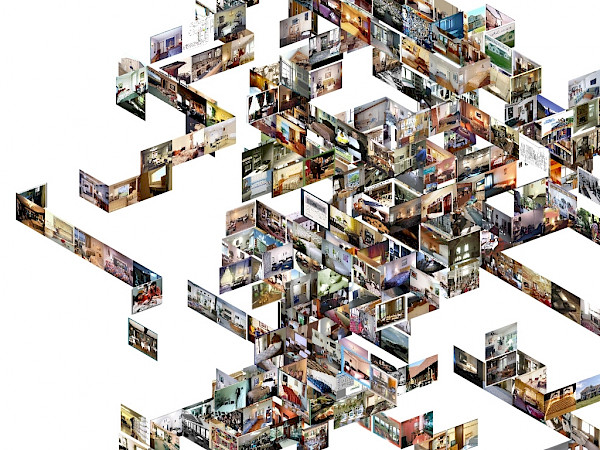

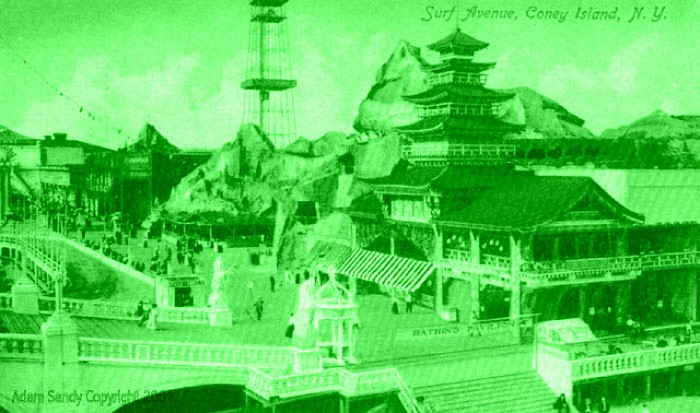

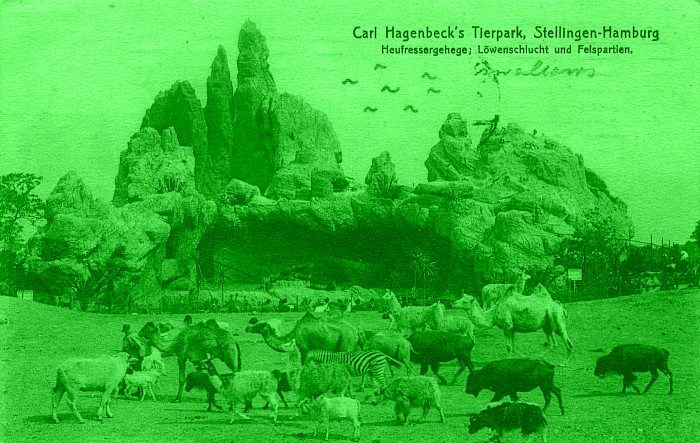

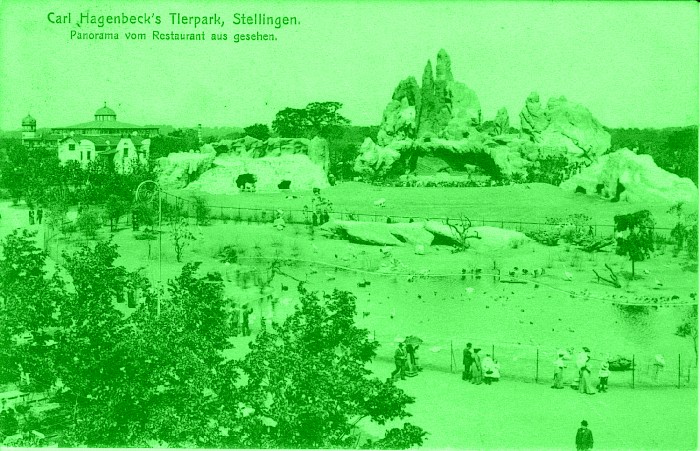

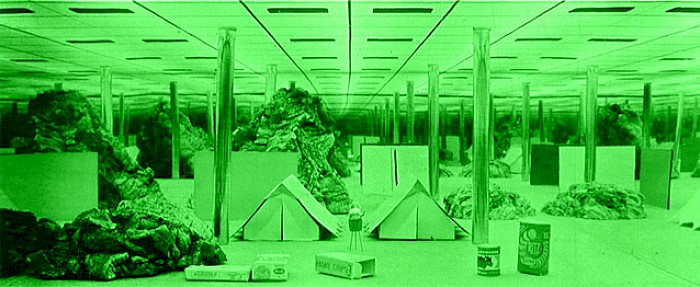

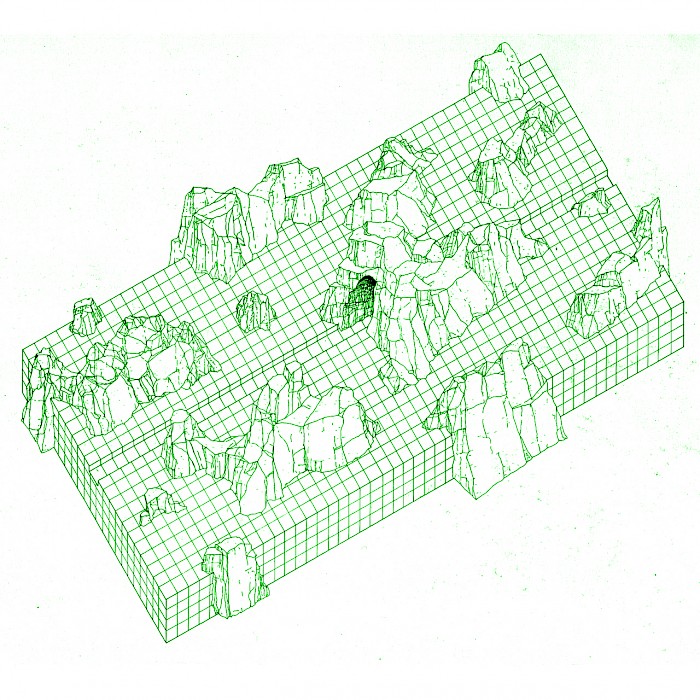

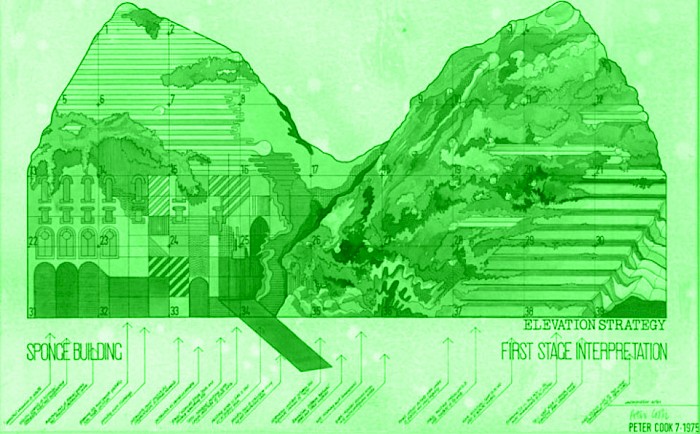

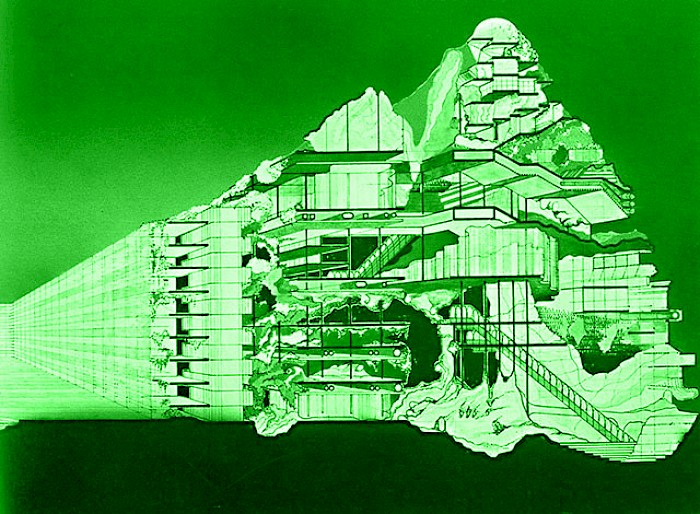

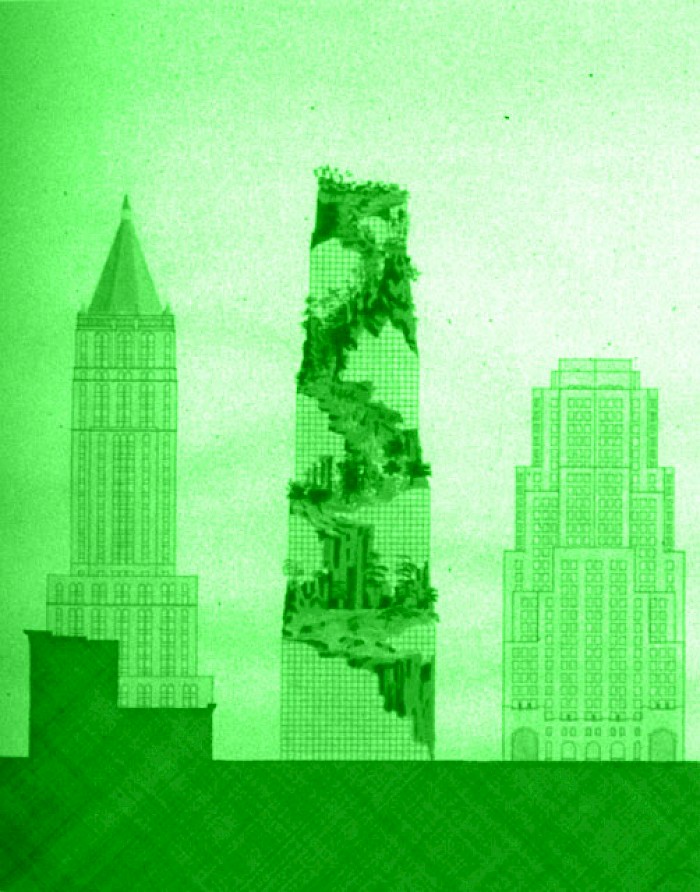

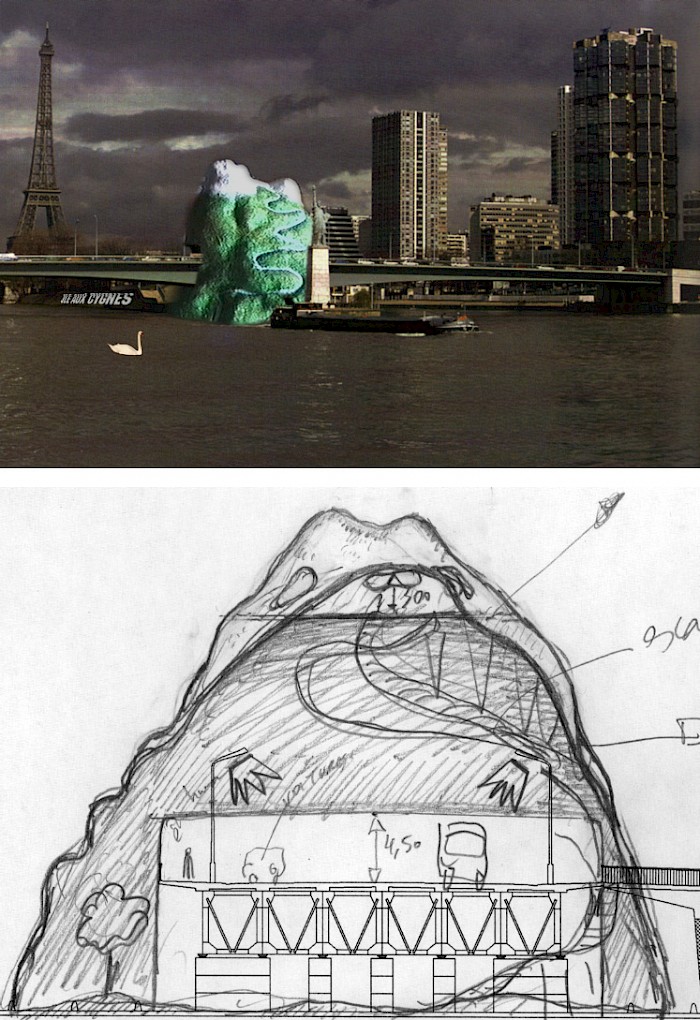

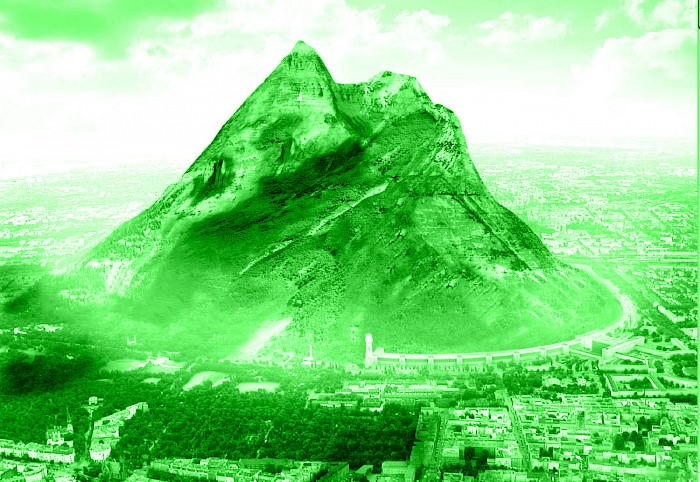

Vincennes zoo in Paris (designed by architect Charles Letrosne) continues this tradition of artificial rockeries, but is this case, « no human architecture is present » (André Hermant, « Le nouveau zoo de Vincennes », in L’architecture d’aujourd’hui, n°8, 1934). No pagodas, no Japanese bridges... More generally, it is the constructive logic of the outside world that disappears behind the concrete. The entire natural environment is symbolized by a unique material. The artificial concrete rock is supposed to symbolize, on its own, all the living environments of animals, and melds in a single movement coasts, forests, steppes or mountains.

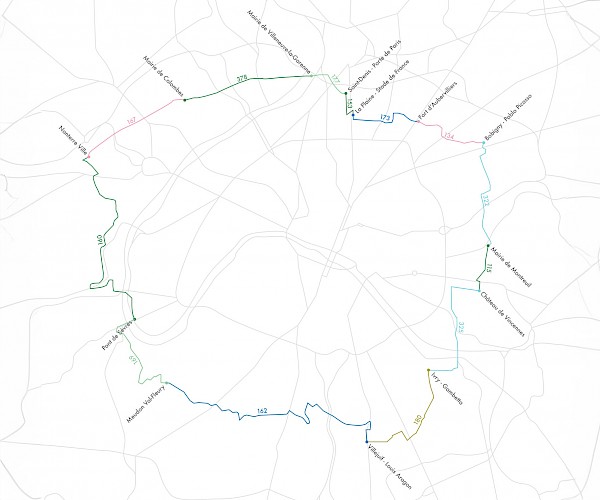

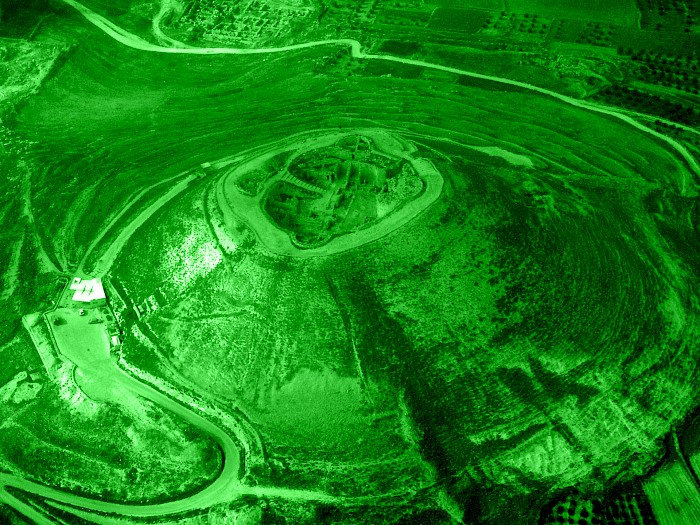

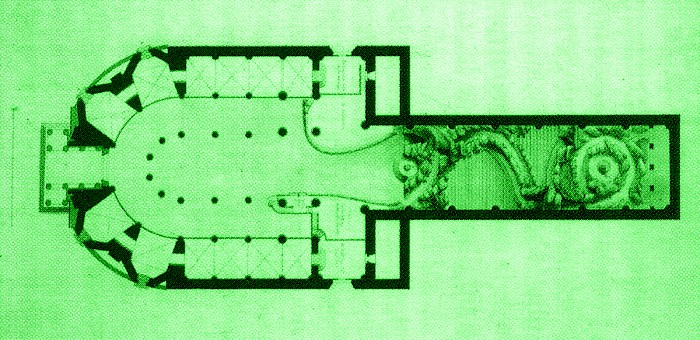

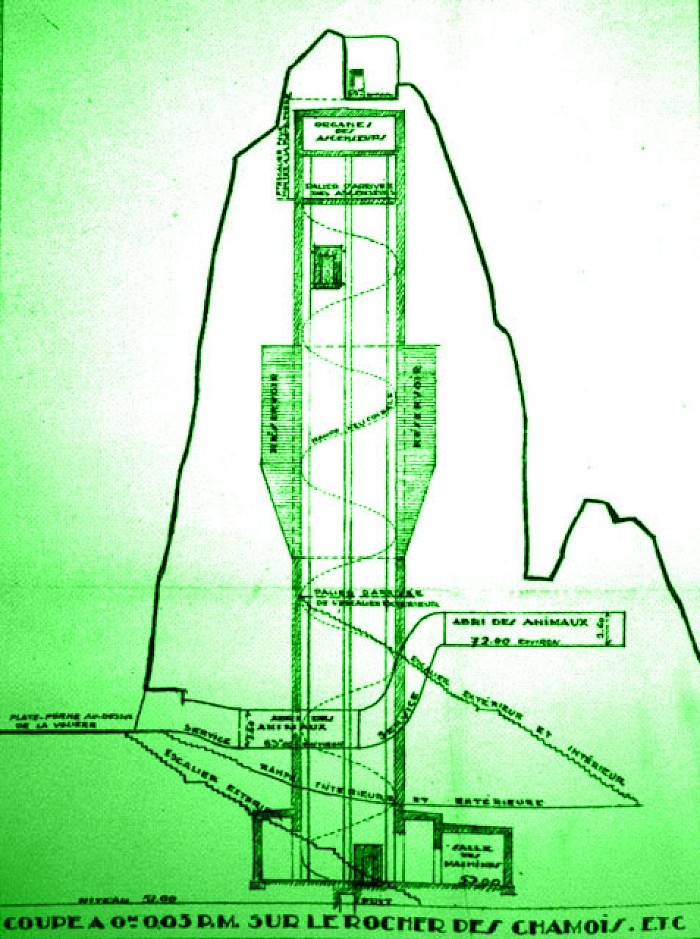

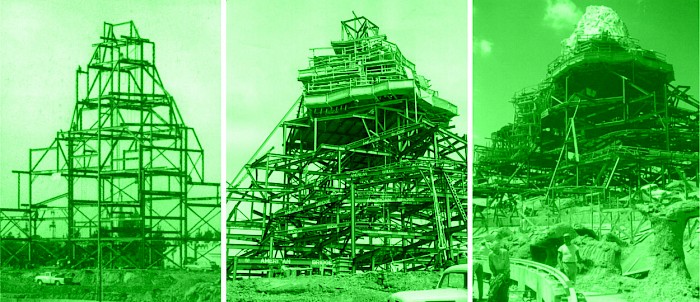

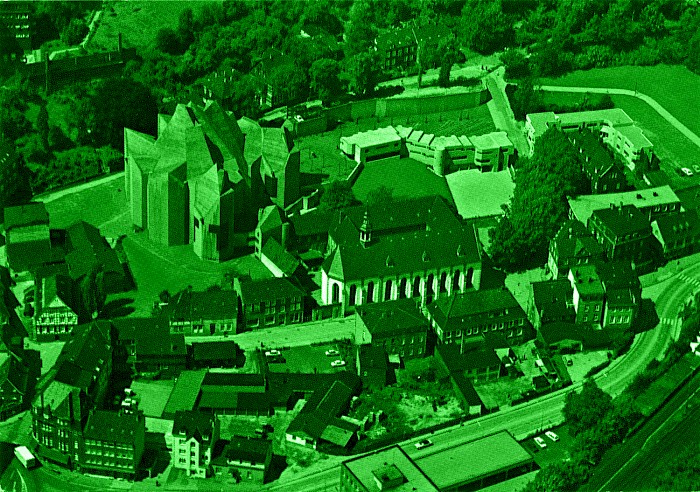

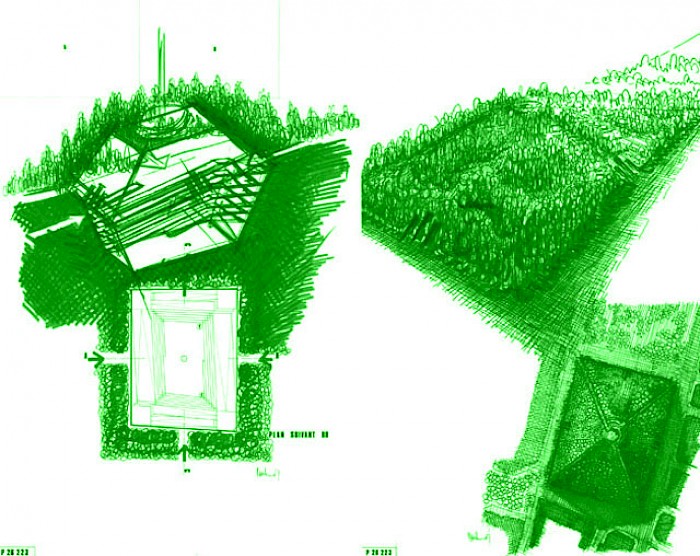

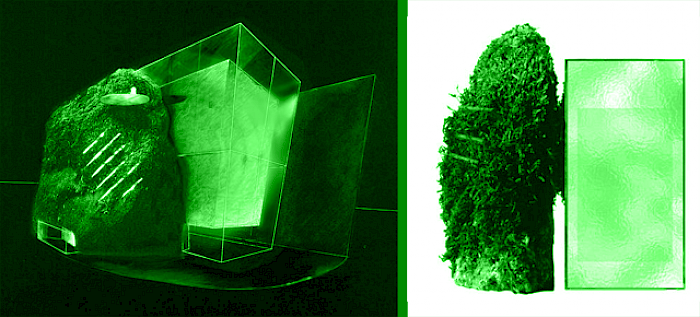

The Vincennes Zoo is inspired by both the Tierpark in Hamburg and the Buttes-Chaumont mountain. The architect Charles Letrosne built the rock between 1932 and 1934. It is entirely made of reinforced concrete, from the frame to its 5cm thick skin.

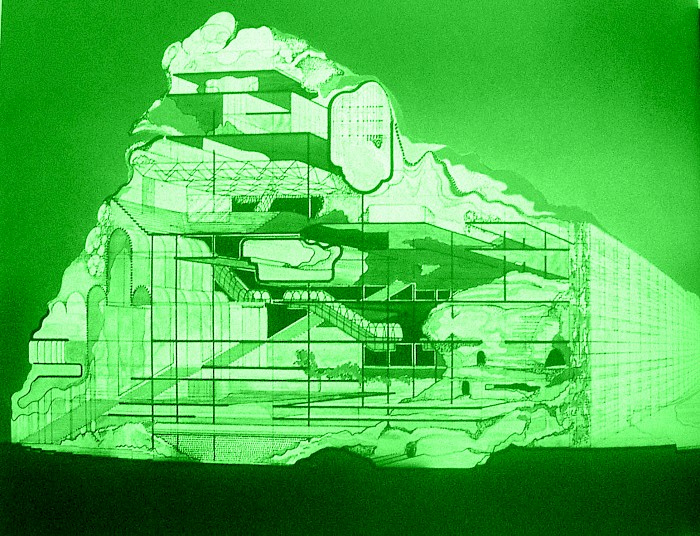

Charles Letrosne erased an recognisable trace of architecture. The environment he created is very perplexing. No architectural eclectism, no curiosity competes with the moutains. The totality of the nature is symbolised in a single basic element, rock, a free natural form whose multiplication ad infinitum renders it abstract. It alone expresses the supposed environment of all the exotic species. Rock is a habitat unit for animals that is splendidly indifferent to the species that it accomodates (which undoubtedly feel as uncomfortable as the penguins of London Zoo in Lubetkin’s pool) and that represents in an identical way coasts, forests, steppes or mountains.

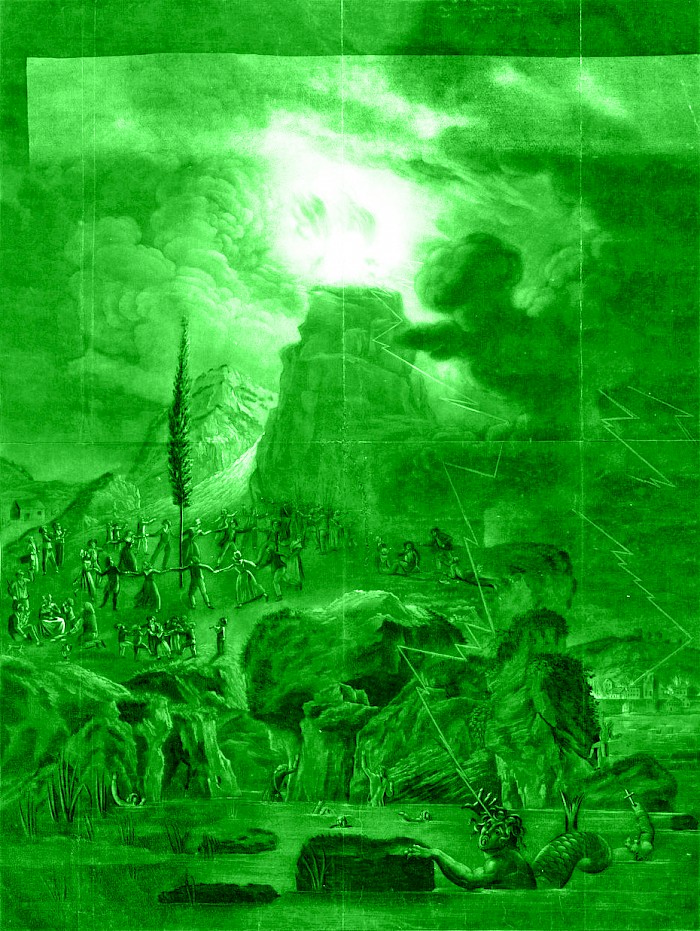

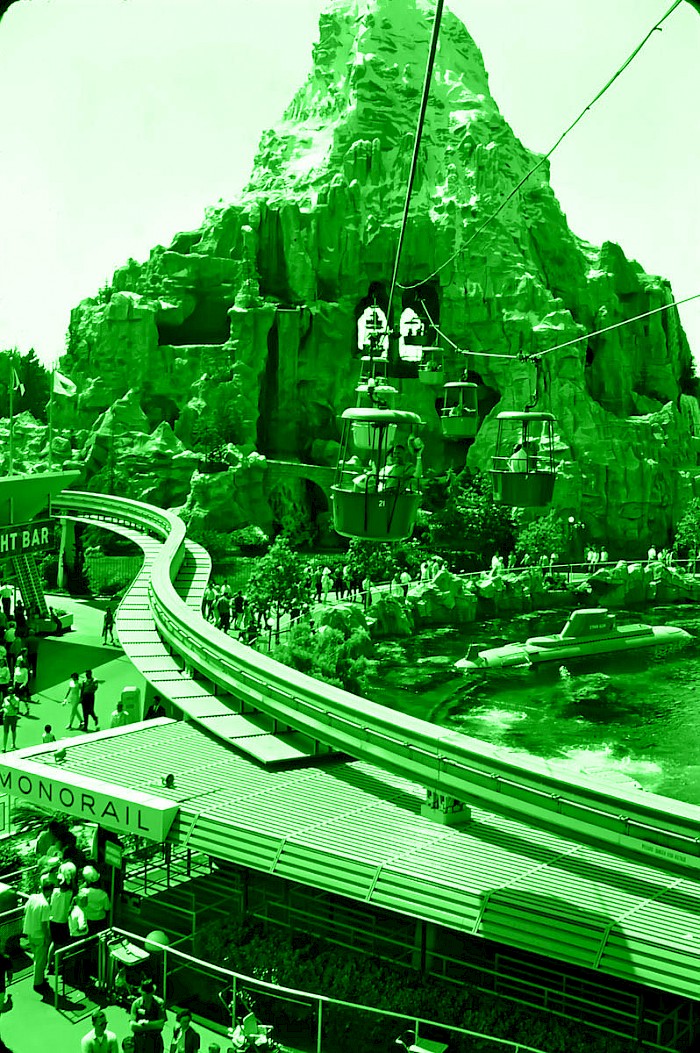

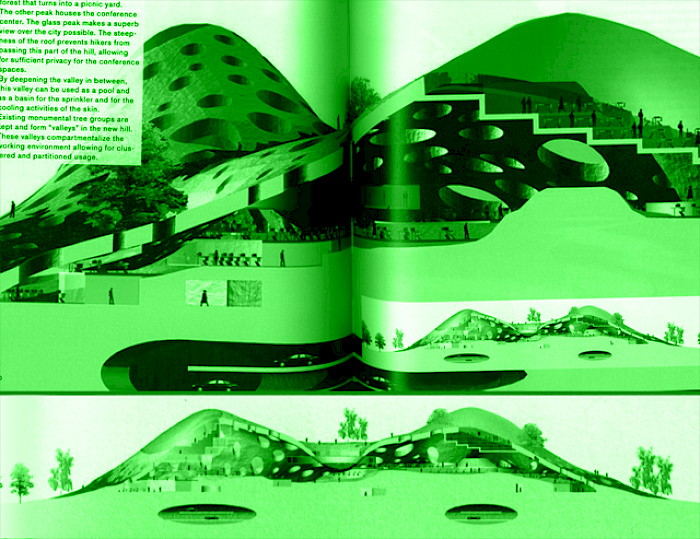

Being neither architectural nor organic, rocks are situated in a vague zone. Whereas in Hamburg, Budapest and London accumulations of different rocks have been represented, here the surface is continuous, as though there were one single cast block – a continuum of reinforced concrete on a bed of wate – reminiscent of the abstract plastic space of the Endless House by Frederick Kiesler (1958). The visitor moves around an integrated, reconstituted environment that unites, in a single cosmic space, moutnains, water, animals, plants and humans.

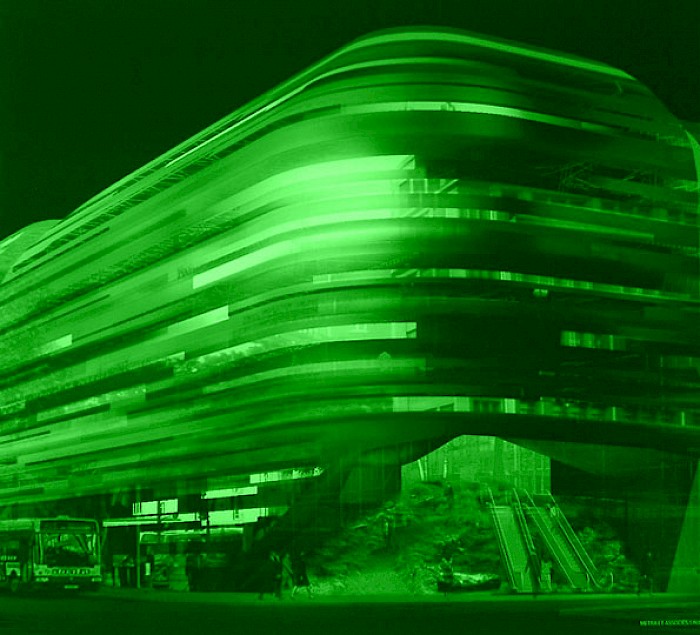

The omnipresent matter seems to trickle through the entire site from the summit of the Grand Rocher, invading the entire space like a grey powder, a continuous monument whose architectural structure would be substituted by the development of an inexhaustible stone. The Zoo de Vincennes stands as a kind of conclusion of the logic of concrete. A uniformising powder, resulting from a chemical process, it spreads with indifference. In appearance, the rocks develop with total freedom thanks to a material that adapts to fit any form, constituting a shapeless and continuous blob in which no construction demand can be distinguished.

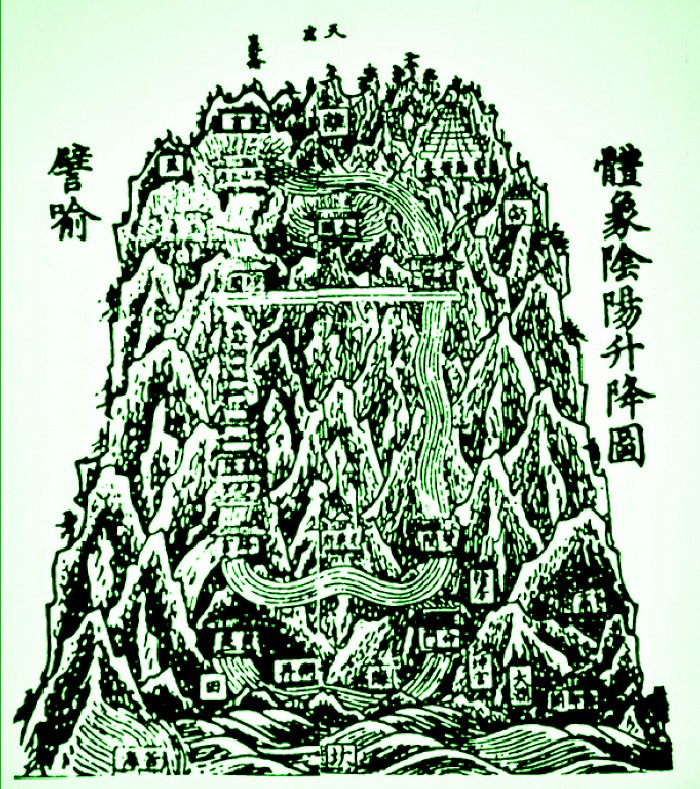

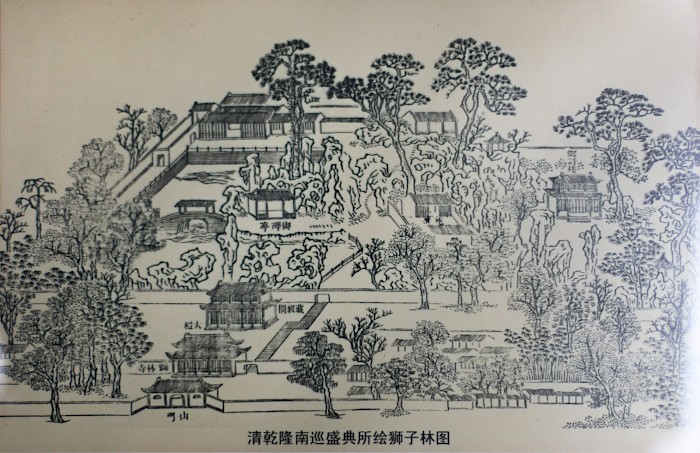

This free artificial material multiplies infinitely, giving rocks a quality of abstraction. While the Chinese tradition spiritualizes the material, the thin concrete skin of the Vincennes zoo achieves the utopia of a total synthesis of the natural world in a single chemical aggregate. It is a place that obliterates matter. An inert, reconstituted, homogeneous and integrated environment unifying mountains, water, animals, plants and humans into a single cosmic space. A uniform grey powder, the result of a chemical process, spreads with indifference, invades the entire space, like a continuous monument, an endless house, pushing the logic of concrete to its limits.

The Zoo of Vincennes fuses two contrasting ways of being in the world: the hyper-presence of the qi of the mountain and the absolute dissemination of its materiality through the infinite deployment of grey goo. This results in a paradoxical place, that seems to simultenaously give life to animals that it houses while reducing them to a powdery state.

Long closed for renovation, it reopened in 2014, massacred by a renovation that caused it to lose almost all of its artificial rocks. The Great Rock has been preserved, but without the ensemble that surrounded it, it has lost its meaning.