For about a century, people have been smiling in photos. Before that, it wasn’t the case. But starting in the 1920s–30s, the click of the shutter began to automatically trigger the risorius, the zygomaticus major, and even the buccinator muscles. This conditioned reflex was born in the United States and gradually spread to the rest of the world. 1

Stéphane Degoutin and Gwenola Wagon, performance La photo :) toute seule.

Photo Université Paris 8 © Audiovisual Creation Service – Patrick Masclaux @pinouck

To be even more sure of the outcome, apps today enhance our smiles—if they don’t generate them entirely—eliminate imperfections, place us in dreamlike settings, while other software selects the best photos from among the thousands we take, corrects them, and shares them with a pleasant musical background. Soon, it may no longer be necessary to take photos or videos at all: AI-powered software will autonomously generate idealized images of our happiness.

Explanation of the "chopstick smile" technique for achieving a wide smile, from “Persuading Yourself with Embodied Smiling,” healthyinfluence.com

Our personal and family photos increasingly resemble stock images. They share the same stereotypical style: clear, neat, ordinary, digestible, easily understood—and depict the same idealized, happy, smiling, polished world. Tensions, racism, poverty, pollution, petty feelings now only appear as devitalized archetypes, emptied of any potential threat. These images are everywhere: they cover city walls, public transport, screens, media; they populate films of all kinds, TV documentaries, ads, magazines, corporate annual reports, clickbait articles, food packaging, tech product boxes, emails, memes, custom greeting cards, construction tarps, and rental car sides…

Omnipresent, stock images nonetheless go unnoticed. They draw little attention. We hardly notice them any more than the strange music that, for about a century now, has graced hotels, animated restaurants, infused shopping centers, filled supermarkets with presence, wrapped around airports, seeped into theme parks, set the mood in offices, energized factories, infiltrated hospitals, helped pass the time in elevators, and filled moments of telephone hold. Flat and bland by design, their goal is to blend into the background. We barely notice the omnipresent soundtrack.

Ambient music and stock imagery are designed to stimulate us without our conscious perception. Their effect is subtle. Their familiar character is engaging and positive, fresh and serene.

Ambient music aspires to be as discreet as air conditioning: a background technology as ordinary as electricity or reinforced concrete. Air conditioning is ubiquitous—in homes, workplaces, airports, train stations, museums, hospitals, cars, trains, buses, planes connecting all these places, and in every country. It is possible to never leave its grasp.

Claudia Schiffer’s real smile, not altered by AI.

Ambient music, stock images, family photos, and air conditioning diffuse a sweet bath around us—an environment in which we float as if weightless, steeped in soft melodies in mall corridors, comforted by photographs of smiling faces and sunny landscapes in magazine pages, soothed by the radiant images of our friends, families, and acquaintances, while our body remains at rest in its comfort zone.

To ensure the result even further, Botox injections tighten our faces, a few scalpel strokes reshape imperfections, implants boost the size of our breasts or buttocks, and gym sessions bulk up our muscles—so that our physical appearance and facial expressions align with the models of representation.

Although the concept of happiness is elusive, fleeting, and unquantifiable, it has become a constant injunction, the sine qua non of any human life. To attain it, we are urged to study self-help techniques, consult life coaches, obey the dictates of positive thinking—and/or imitate the outward signs of well-being. If it proves too difficult to achieve, various technologies of compulsory happiness generate a backdrop that automatically integrates into our lives and reshapes them to match the idealized version found in stock images and ambient music.

It’s life on a green screen.

This text examines the various methods that help make positive thinking concrete and material. The ways of manufacturing a smile can be direct and commanding ("Say cheese!"), medical (cosmetic surgery, which literally fixes the smile onto the face), simulated (artificial intelligence), or all three at once.

Stéphane Degoutin et Gwenola Wagon, performance La photo :) toute seule. Photo Université Paris 8 © Service création audiovisuelle – Patrick Masclaux @pinouck

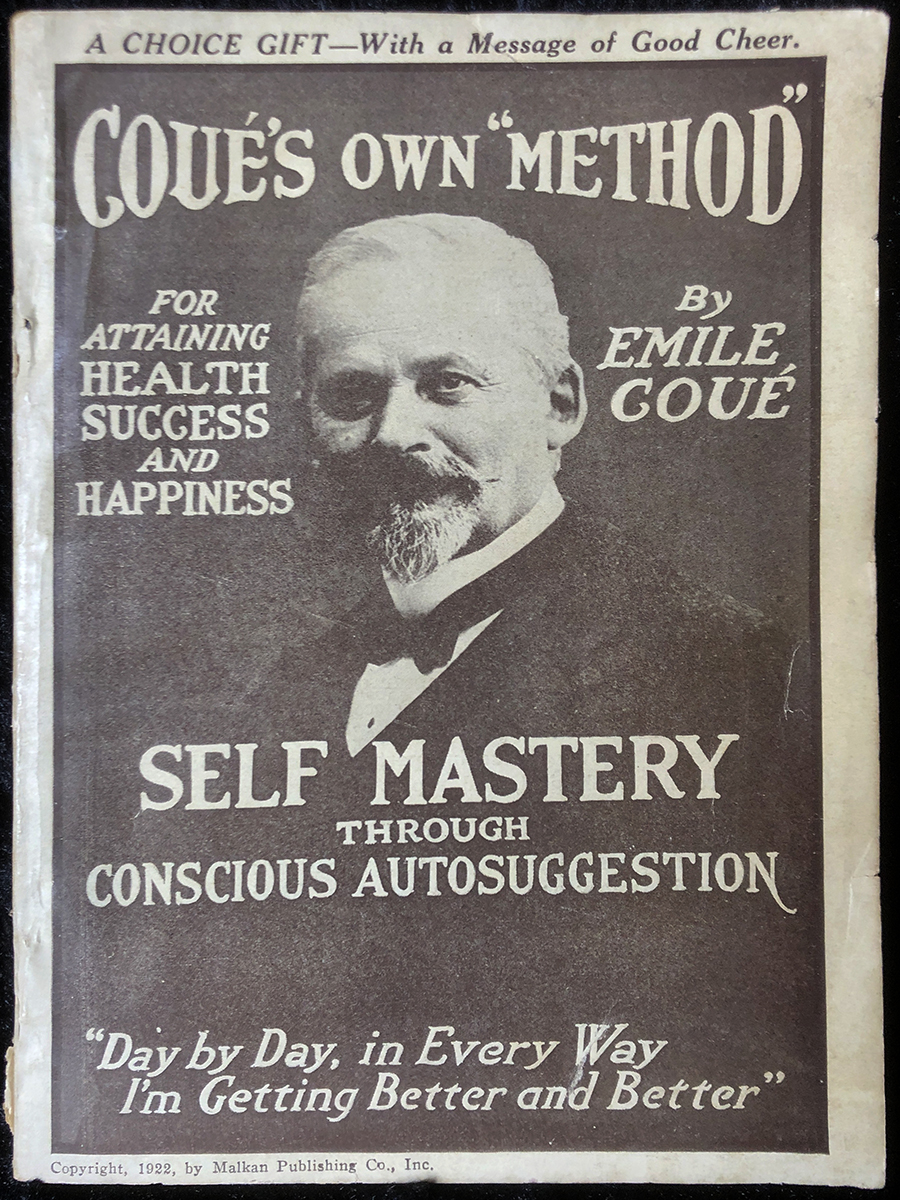

Coué invents mass-produced happiness

"Strictly speaking, you know, invention doesn’t exist. It’s just about amplifying what already exists." — Allie Fox, character from the film The Mosquito Coast. 2

"Coué is none other than the little man who held the secret of happiness, the stubborn little old man who, suitcase in hand and without fanfare, went from capital to capital spreading his famous health formula: 'Every day, in every way, I’m getting better and better.' A formula which, to many, seemed like some kind of English taffeta to be applied with faith to humanity’s immense misfortune! [But] Coué, the patient and keen observer of life, had discovered more than a magic or miraculous formula: he had uncovered a law of the mind." — Alphonse de Châteaubriant 3

Collective listening to the voice of Émile Coué. Stéphane Degoutin and Gwenola Wagon, performance La photo :) toute seule.

Rencontres EUR ArTeC, Maison des métallos, Paris, November 15, 2023. © Audiovisual Creation Department – Patrick Masclaux @pinouck

In Troyes, in the early 20th century, pharmacist Émile Coué almost accidentally discovers the secret to happiness. He observes that when he sells a medication with a promise of healing, people imagine they will recover — and they do. Conversely, those who believe they will worsen tend to deteriorate. It is therefore better to believe improvement is possible.

"If, while being ill, we imagine that healing will occur, then it will, if it is possible. If not, we will still obtain the maximum possible improvement." — Émile Coué

Émile Coué in his pharmacy, in Troyes. Late 19th century.

Screenshot from the film Deep Smile, Stéphane Degoutin and Gwenola Wagon, 2024.

Beyond physical healing, he extends this principle to general well-being: you only need to repeat to yourself that you are happy, wealthy, attractive, and healthy — even if it’s not true — to become so. A thought, once mentally embraced, can become real. He discovers the power of autosuggestion. 4

![Dr [Emile] Coué en Amérique Dr [Emile] Coué en Amérique](https://d-w.fr/img/photo-sourit/06-coue-usa.jpg)

Dr [Emile] Coué in America

(Keystone): [press photograph] / [Agence Rol], 1923. Gallica.bnf.fr

This technique, simple yet effective, sees brief success in France but spreads like golden powder in the United States, where Coué is triumphantly received (let’s not forget that the pursuit of happiness has been enshrined in the U.S. Declaration of Independence since 1776). Yet Charles Baudouin, a disciple of Coué, laments how his ideas are distorted:

"The misfortune is that the modern public wants panaceas, to be acquired quid pro quo, at market value. They bring with them the spirit of industrialism and Americanism to which they are accustomed. They want to purchase healing as they would a mass-produced gadget." 5

Émile Coué’s smile, discreetly hidden behind his moustache.

Happiness marketing in 1922.

New Thought: material success, religion, and positive thinking

Coué’s discovery didn’t appear out of nowhere. He inherited from the Nancy School 6 and had practiced hypnotic suggestion — though he later abandoned it, finding the method too vague.

Another major influence was the New Thought religious movement that emerged in the U.S. in the late 19th century. It promoted an idealistic and optimistic view, centered on personal well-being, health, and material success — values that would far outlive the movement itself. 7

New Thought already encouraged repeating optimistic phrases alone and endlessly, such as: “I have succeeded, I will succeed, I must succeed, nothing can stop me, I will make a success of my life… My will is strong, no one can resist my influence. I can control others.” 8 By the late 19th century, the idea was present on both sides of the Atlantic: the psychologist and physician Pierre Janet reported seeing depressed women at the Salpêtrière hospital in Paris carrying similar phrases in their corsets. 9

It originates with Phineas Parkhurst Quimby, mentor to Emma Curtis Hopkins and Mary Baker Eddy. As early as the 1840s, Quimby realized that belief in one’s own health could itself be curative.

Mary Baker Eddy preaching New Thought. United States, late 19th century.

Screenshot from the film Deep Smile, Stéphane Degoutin and Gwenola Wagon, 2024.

"Throughout the twentieth century, the central premise of New Thought — that the mind can change reality — captivated millions of Americans […] through popular literature, from Emmet Fox’s The Sermon on the Mount, a 1930s bestseller still in print, to Norman Vincent Peale’s The Power of Positive Thinking, which in 1954 outsold every other nonfiction book except the Bible." 10

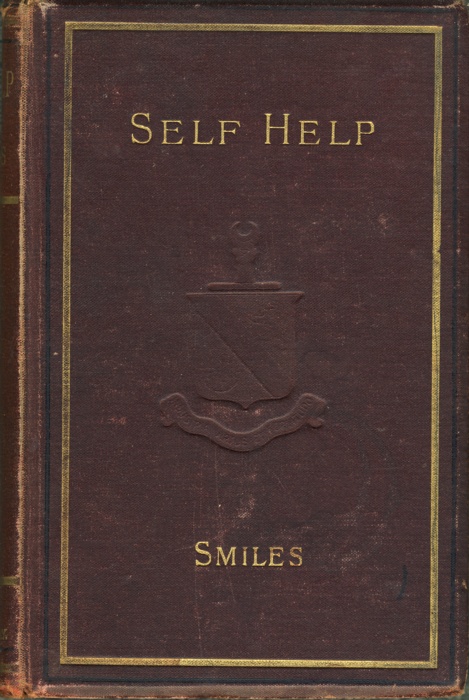

Samuel Smiles invents “self-help”

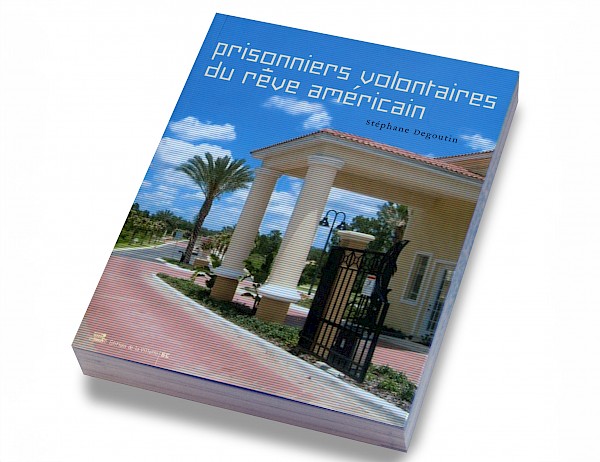

The ground was also prepared by the 1866 bestseller Self-Help by British author Samuel Smiles. Dubbed “the Bible of mid-Victorian liberalism,” this method targeted primarily the working class, encouraging them — as the title implies — to rely on themselves, in a logic highly compatible with capitalist development.

However, Smiles still advocated for the work ethic. Coué’s stroke of genius was to discard all that: his method relies solely on belief, requiring no self-improvement, no effort toward others. The key to happiness is simply to simulate it: believing happiness is possible is to be happy.

Working-class audience listening to a lecture by Samuel Smiles. Liverpool, circa 1860.

Screenshot from the film Deep Smile, Stéphane Degoutin and Gwenola Wagon, 2024.

An early edition of Samuel Smiles’ Self-Help.

And this belief doesn’t even need to be based on strong reasoning. Witness Coué’s childlike rhyme, which he recommended repeating daily in a relaxed state as the key to all healing: “Every day, in every way, I’m getting better and better.” The only requirement is to believe it works.

From this flow the infinite variants and countless zealots of positive thinking and "self-help" 11, from Dale Carnegie 12 to Napoleon Hill 13, Norman Vincent Peale 14, Stephen Covey 15, and Carol Dweck 16. All endlessly repeat, in books and videos, the same mantras (“Listen to yourself,” “You’re doing great,” etc.), endlessly varied.

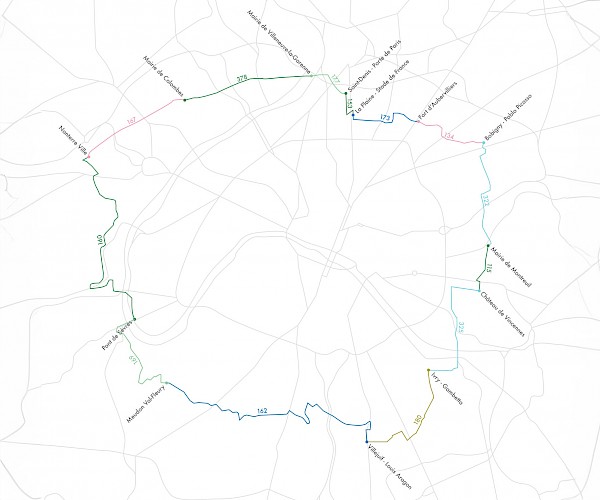

Detail from a collection of 1,700 book covers with the word “Happy” or “Happiness” in their titles.

Stéphane Degoutin, 2023. Vimeo link: https://vimeo.com/916707630

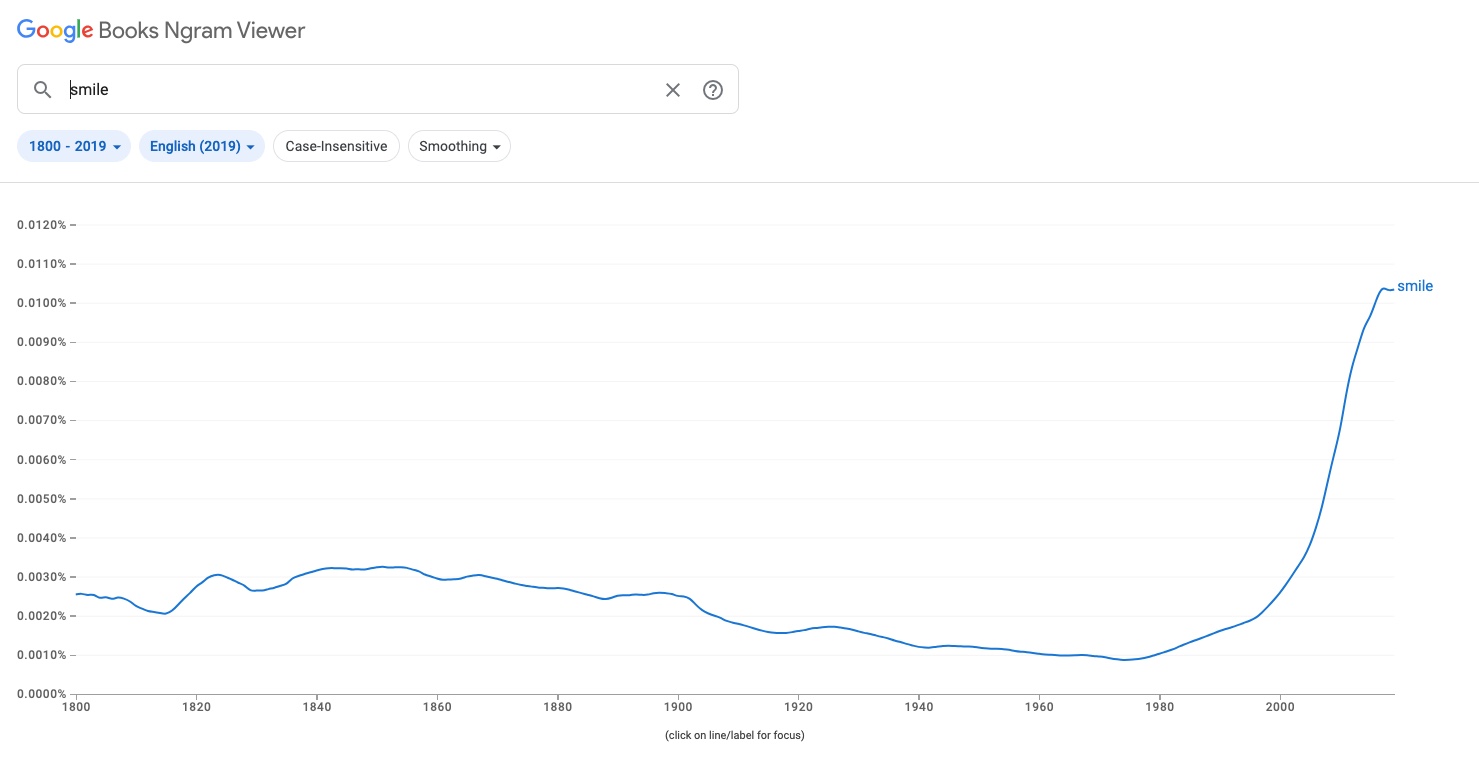

Source: Google ngram viewer, 2024.

« Selon le catalogue de la Bibliothèque nationale de France, la quantité d’ouvrages dédiés au bonheur croît dans les années 1970, en valeur absolue, mais également par rapport à la production totale d’imprimés. » 17 On observe une évolution similaire pour l’utilisation du mot « smile » dans les livres de langue anglaise.

"According to the catalog of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the number of books dedicated to happiness increases in the 1970s, both in absolute terms and relative to total book production." 17 A similar trend appears in the use of the word “smile” in English-language books.

We cannot underestimate the reach of this way of thinking. Beyond the folklore of self-help literature, positive thinking permeates the entire U.S. cultural fabric — and by extension, spreads globally.

As Charles Baudouin already noted, we are entering the era of happiness as a mass-produced commodity.

The "Pan Am Smile", on a Pan America advertising poster, 1950s.

Gwenola Wagon and Stéphane Degoutin demonstrating the "chopstick smile" during the performance “La photo :) toute seule”© Photos by Université Paris 8 / Audiovisual Creation Service — Patrick Masclaux @pinouck

Analysis of the markers of the “Duchenne” smile (or “authentic” smile) as opposed to the “non-Duchenne” smile (or “forced” smile), from Yevgen Bogodistov and Florian Dost, “Proximity Begins with a Smile, But Which One? Associating Non-duchenne Smiles with Higher Psychological Distance,” Front. Psychol., August 10, 2017.

Kodak Invents the :)

In the 1920s, just as “Couéism” was being exported abroad, another key transformation took place in the U.S.: advertisers stopped using guilt-inducing arguments (like “You’ll look old if you don’t use cream X,” or “You’ll end up broke without bank Y…”) and instead began highlighting the positive, joyful aspects of the lifestyle associated with the products being promoted: “Consumer happiness became the prime directive of advertising 18.”

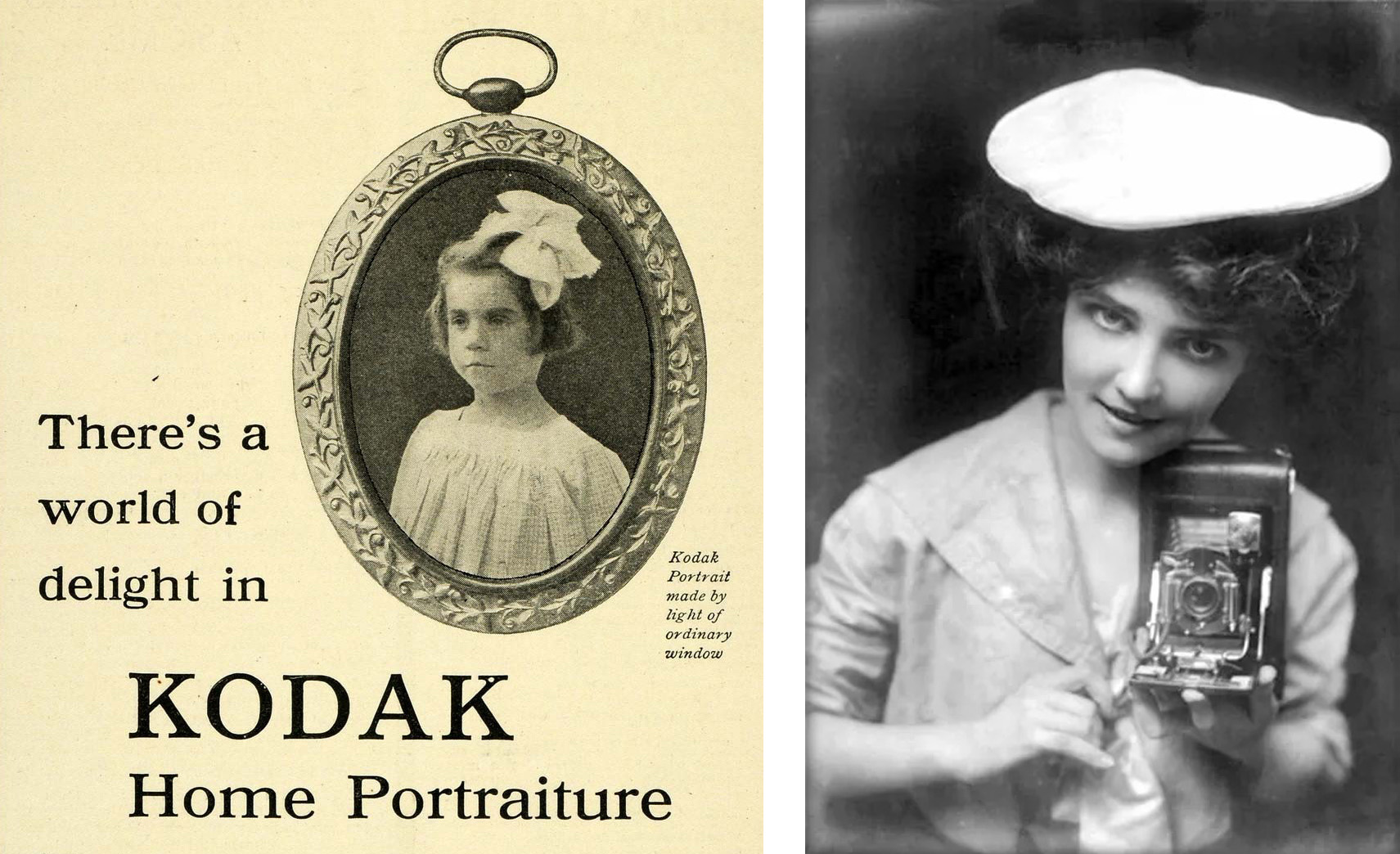

One company that capitalized on this trend was Kodak. In her article “Why We Say ‘Cheese’: Producing the Smile in Snapshot Photography” 19, Christina Kotchemidova explains how advertising for Kodak’s instant camera revolutionized how we present ourselves to others, by inventing the photographic smile.

Left: Kodak ad from 1906. Although it promises “a world of pleasure,” a successful photo wasn’t yet dependent on a smile. Right: 1909 ad. The Kodak Girl smiles.

In its magazines and ads, the company produced imagery expressing the joy of being alive by consistently showing photographs of happy life moments: celebrations, Christmas, birthdays, weddings, travel… They chose as a mascot the Kodak Girl, a young woman always smiling.

Instant cameras launched a revolution: to succeed in photography meant capturing the fleeting, precious moment of a smile. Amateur photography would henceforth spread smiling around the globe, with the aim of spreading joy—even linking it to consumerism. Kodak embedded the camera into the “happiness system.”

Smiling sells. Advertising links emotion to product, transforming not only the act of buying (the camera, its film, and processing) into a pleasurable gesture, but also markets the production of photographic images as potential moments of happiness. Every purchase is associated with the emotion of happy consumption. By implication, someone who does not consume is unhappy—or worse, unrepresentable.

Kodak Girls from different eras.

After WWII in Italy, the invention of the modern photo-novel—drawing inspiration from cinema and comics—established the aesthetic of the smile in photos “by adopting the sentimental trope of individual happiness conveyed by American productions of the time.” (Yet the photo-novel never caught on in the Anglo-American world) 20.

By extension, the entire United States embraced the symbolism of happiness represented in images by its most recognizable feature: the smile. From factory workers praising productivity to housewives showing off new appliances, the radiant smile spread like a decal, from advertisements to family photos. Faces beamed with happiness during a new house purchase, lawn mowing, or car ride. And that same frozen smile helped export to the world a lifestyle based on consumption, marketing, and advertising, as depicted in the film My American (Way of) Life by Sylvain Desmille. Over archival footage, the character Jeff Stryker explains how his generation tried to change the world with and through images of happiness:

"These are old images, snippets of happiness stitched into family life, patches of memory darned into the fabric of time. These images tell my story. They are me. And they belong to me. We will all recognize ourselves in them. Because after WWII, the American model sought to assert itself globally. Our lifestyle—the American way of life—became a reference point. A showcase, a culture, a dream, and a societal model aimed at countering communist ideology.

Throughout the Cold War, for fifty years, grand history and our personal stories became deeply intertwined. We shared the same desire to write a world in our own image: happy, prosperous, and triumphant, where parents would always make their children proud.

But sometimes, even our most beautiful dreams slip away.

My name is Jeff Stryker, and this is my story." 21

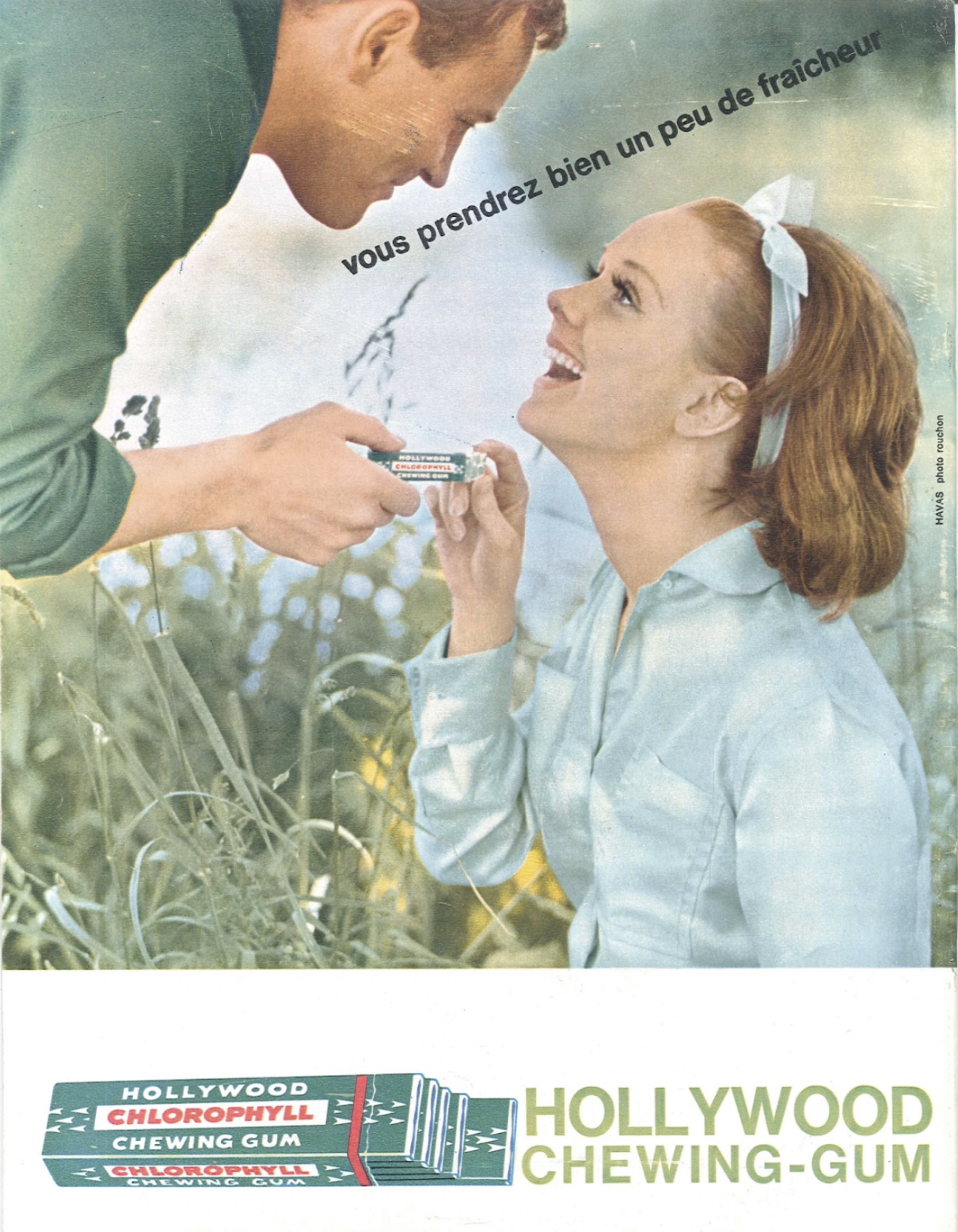

Advertisement for Hollywood chewing gum.

This shift in paradigm wasn’t just about visible imagery but also about values. Until recently, happiness was seen as the domain of fools or a tool for mass control (notably in Brave New World by Aldous Huxley 22). One was supposed to accept reality and shun fantasy to avoid suffering. It was uncharitable to be happy among the unhappy—and especially not to flaunt one’s happiness in photos. After WWII, the paradigm flipped: ethics of duty, merit, bravery, and courage gave way to individual success, well-being, and personal development. Happiness became the norm, replacing the “values” of past generations.

The Sound of Happiness

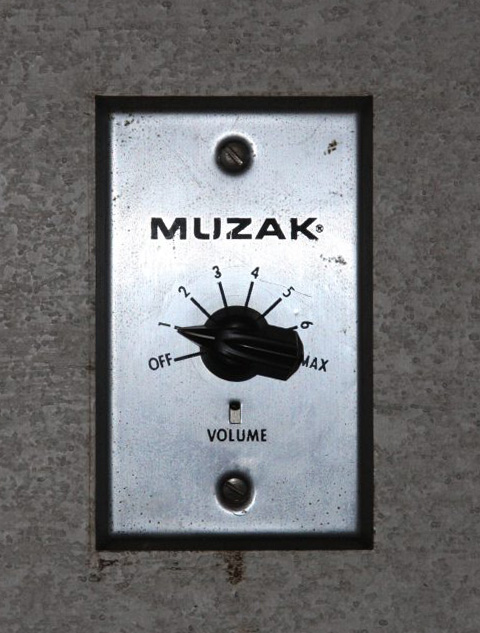

“Muzak,” named after the leading company in the field 23, also dates from the early 20th century. The name Muzak is a mash-up of music and Kodak (just like “motel” comes from motor and hotel), and Muzak targets the smile as much as Kodak did.

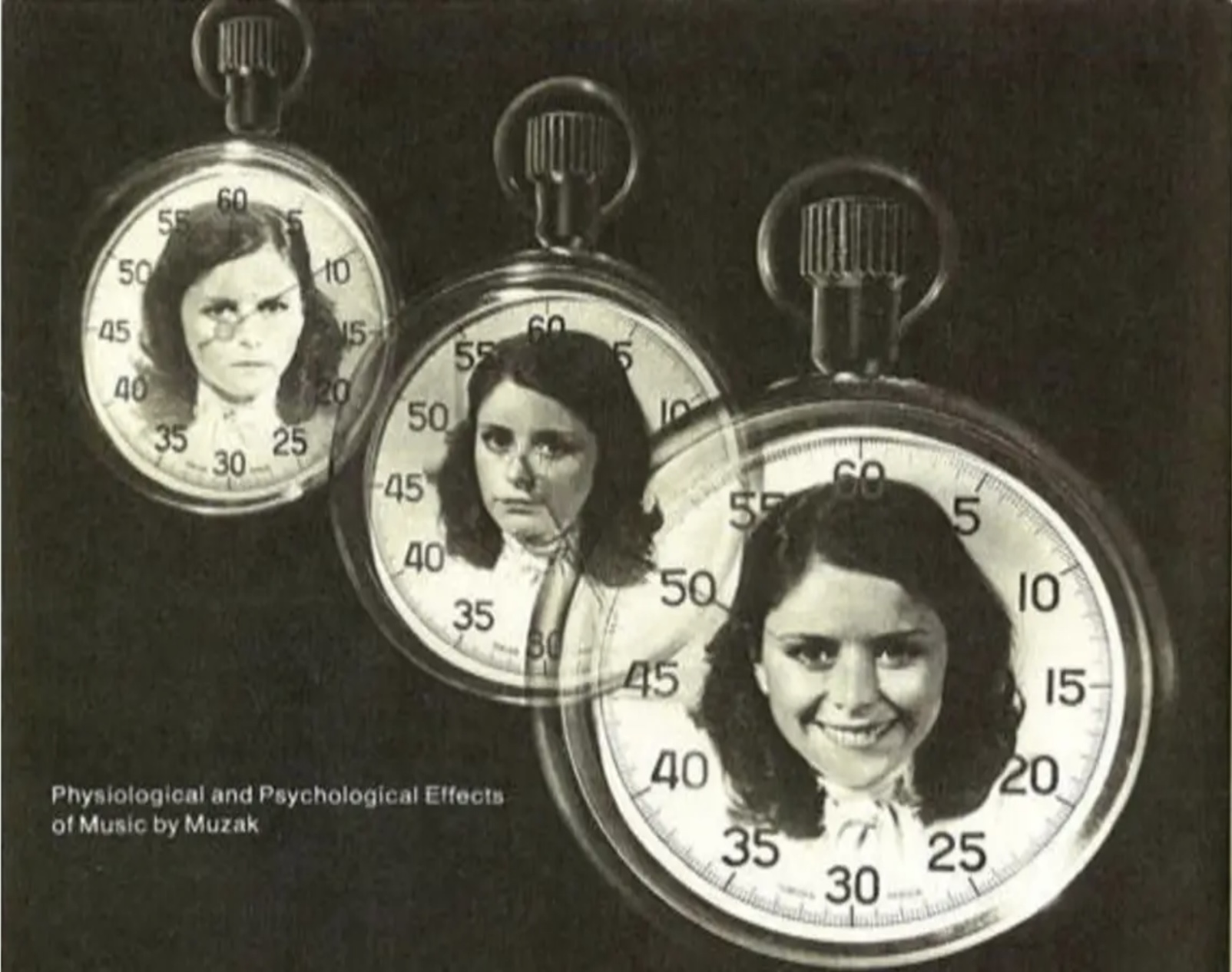

An advertisement showing how Muzak generates smiles at work.

Muzak Inc. marketed endless playlists meant to help workers focus, foster a consumer-friendly atmosphere, or accompany leisure activities. The company claimed it could measure the effect of its product on the productivity of employees, shoppers, or vacationers through extensive studies, data analysis, and internal reports with poetic names like Effects of Muzak on Industrial Efficiency, Effects of Muzak on Office Personnel, Application of Functional Music to Worker Efficiency, Research Findings on the Physiological and Psychological Effects of Music and Muzak, etc. 24

To increase productivity, Muzak had to create optimal conditions: relaxation and happiness.

Muzak’s offices in the 1960s.Generated image, from the performance Personal Development for Houseplants, Stéphane Degoutin, 2017–2024.

Because the idea of manipulating people for productivity was unpopular, Muzak Inc. preferred to say it made employees happy. Listening to Muzak at work became a form of self-improvement, a method for generating harmony.

Muzak sold background happiness.

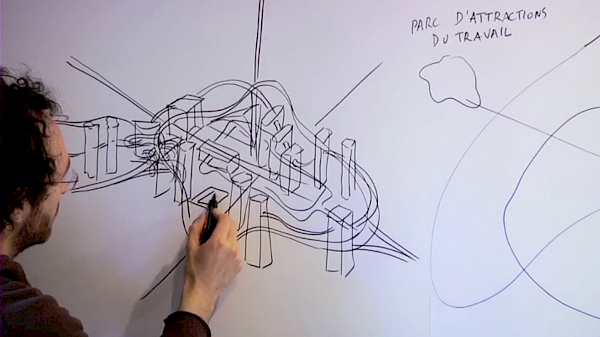

Muzak sits precisely at the intersection of productivity ideology, compulsory happiness, and the strange yet widespread mechanistic/deterministic belief that a complex stimulus in a complex environment can yield a simple effect.

Muzak Invents Music Without Music

Muzak prides itself on being as discreet as possible. As the director of Muzak said in the 1970s:

“We specialize in music designed for non-entertainment purposes. We are specialists in the psychological and physiological application of music. Any form of art requires intellectual or emotional engagement—thus, conscious participation. What we do is exactly the opposite. We play background music that sets the mood of the environment. We play it so that you hear it, but without listening to it.”

— Umberto V. Muscio25

The listener should perceive Muzak without paying attention to it: it is not meant to pass through the filter of consciousness. More than music, Muzak is an environmental parameter, like wallpaper or air conditioning.

“Muzak was founded on an idea that, in its own way, is reminiscent of the luminous paradoxes of Zen: boring work is made less boring by boring music.”

— Anthony Haden-Guest 25

Music as an environmental parameter: a Muzak control box.

We enter here the gray zone of music.

This music is not limited to workplaces. It spreads everywhere. It is called background music, elevator music, hold music, ambient music, music by the mile. English has a sprawling vocabulary for it: mood music, elevator music, background music, wallpaper music, hold music, piped music, canned music, supermarket music, light music, easy listening.

Joseph Lanza, author of the definitive book Elevator Music, offers an intriguing interpretation: the subject of background music is not the music itself—it’s us. Muzak is the soundtrack of a film with no film reel, a film that merges with life and of which we are the protagonists:

“Background music shifts music from figure to ground, to encourage peripheral listening. (…) It inspires us to structure our messy and boring existence into film scenes, whose soundtrack alternately follows and anticipates our thoughts and actions. Background music reinforces the suspicion that we are living in a dream.”

— Joseph Lanza 26

Mood Images

Just as Muzak is produced industrially, slips by without catching the ear, and is stripped of any unique elements that might grab attention (no vocals, catchy melodies, strong rhythms, wild tempos, syncopation, solos, improvisations, strange instruments, etc.), stock photography or image bank photos 27 are produced industrially, slip by without catching the eye, and are devoid of any singular detail or hook. They exclude overly distinctive, recognizable, or atypical faces… 28

Like Muzak, stock images are characterized by the absence of surprise. They are the visual equivalent and share the same traits. We could call them “mood images.”

Whereas music and art seek to balance expectation and surprise, harmony and disruption, Muzak and stock photos exist solely on one side of the divide: always-fulfilled expectations and perfect harmony. If beauty is, in some way, “always strange” (Charles Baudelaire), Muzak and stock images seek the opposite: the absence of strangeness, the absence of surprise. Yet they are created by professionals using the best available equipment, strictly following lighting and composition rules. These are non-intrusive music and images.

Our personal images are increasingly starting to resemble stock photos. Or perhaps it’s the reverse.

Most stock images are extremely mundane: they depict simple, obvious situations. Among the most requested are daily life scenes: generic, standardized, stereotyped, simplified, and exaggerated. Archetypal people perform easily identifiable actions. The actors express emotions with codified and easily understood gestures, much like photo-romance novels: the jealous woman sits on the bed with her head in her hands, while her husband, in the background, arms crossed, looks on absent-mindedly. Children eat breakfast with wide eyes and big gestures. These are generic images “in the sense that they can be used by many different businesses. They have almost universal appeal.” 29

Just like in our personal photos, stock photos are subject to the dictatorship of the smile. In this world, everyone smiles all the time.

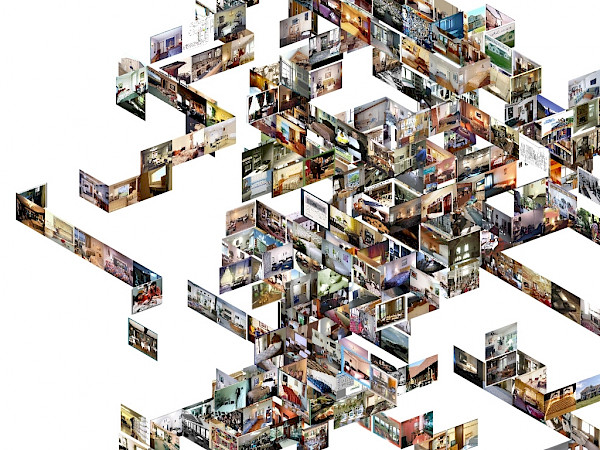

The vast majority of close-up stock photos of smiling faces show white women’s mouths. Stéphane Degoutin & Gwenola Wagon, Atlas du nuage, 2022.

The Uncanny Strangeness of Banal Images

It seems to us that the common feature of all these images is that they do not try to hide their artificial nature. On the contrary, the staging is always obvious. These images must appear fake so we interpret them as illustrations rather than news photos, artistic creations, or real-life moments. 30

Stock photos offer a form of simulation. A real parallel world is unfolding here, one where everything is smooth and visibly false. Every real-world element—every action, idea, lived experience, or transaction—has a twin in an image bank. All is transmuted through the semantic codes of stock photography.

This world appears close to ours, since it aims to modestly illustrate reality. Yet it doesn't seem governed by the same laws: the people depicted do not resemble us. They are too generic; they lack substance. The situations are too obvious. The smiles seem fake. Even the most banal images emit a certain strangeness.

The same archetypes appear in AI-generated images:

“Because generated images rely on a corpus of blatantly obvious imagery, they can’t really be ambiguous or ambivalent, even when you ask them to be; they always try to sell you their accuracy compared to the statistically likely version of the prompt. (…)

Worse still, everything is presented as if it’s for sale, like pornography or advertising. Even when you ask a model for a style transfer—an image in the style of Ingres, for example—you get the commercial version, the ‘platform realism’ version of what ‘Ingres’ conceptually means. It’s impossible to request images that don’t look like advertisements, because the logic of symbolic communication in advertising is already baked into the way the models fundamentally work.”

— Rob Horning 31

In her article AI and the American Smile 32, Jenka comments on a series of 18 images posted by m0us316 on r/midjourney, “34 Time Period Selfies: Time traveler shows soldiers, warriors, and people from various time periods what a ‘selfie’ is. (V5).” It shows Native Americans, Japanese samurai, French WWI soldiers, etc.—all posing for selfies. What stands out is their huge, out-of-place “American” smiles. That’s because Midjourney was trained on smiling American selfies.

Time Period Selfies: Time traveler shows soldiers, warriors, and people from various time periods what a “selfie” is. (V5).

If AI-generated smiling images resemble stock photos, it’s because they are built from them, recombined, endlessly producing more of the same.

But stock photos were already based on advertising aesthetics. They adopted its full iconography: polished visuals, clear messages, no ambiguity, ubiquitous smiles...

“(…) advertisements always evoke, implicitly or explicitly, the idea of happiness. They invoke it to intensify the desire of potential customers. By repeating the same themes and building a consensus around the legitimacy of pleasure and happiness, advertising detaches them from guilt and dissolves the moral opposition between passive consumption and active self-realization; it participates in the conversion to happiness.” 33

Hollywood—and World War I—Invent Plastic Surgery

“At the moment of incision, I give thanks to the one who, lying in front of me in total trust, places the destiny of their beauty in my hands.”

— Suzanne Noël, 1924 34

Suzanne Noël at work.

Since the early 20th century, the film industry, merged with show business, has crafted and maintained celebrity through the attractiveness of their media representation. According to Edgar Morin, the role of the star “becomes psychosocial: it polarizes and fixes obsessions. These dreams, though unable to fully materialize, still surface in our concrete lives and shape our most malleable behaviors.” 35

With a near-hypnotic insistence on the close-up, cinema magnifies the allure of the face, shapes the icon status of stars, and fuels Hollywood studios’ branding. The history of the remodeled face coincides with the display of marketable appearances and the commercial pressure on public figures.

Plastic surgery is ancient 36, but before the 20th century, it was primarily used to reconstruct damaged faces. The massive number of WWI soldiers returning from the trenches with facial injuries led to rapid progress in reconstruction techniques. It wasn’t just about fixing noses or ears but rebuilding entire faces blown apart or bodies burned by gas.

At the same time, the entertainment industry used these techniques to sculpt star faces. Surgeon Suzanne Noël, for example, performed Sarah Bernhardt’s second facelift 37 before treating disfigured soldiers at Val de Grâce 38. These back-and-forths between showbiz and wartime surgery accelerated technical innovation.

Cosmetic surgery literally draws the image of happiness onto faces: the surest way to comply with the obligation to be happy is to seal a smile onto the face.

Face, :), Glory, Power, Beauty

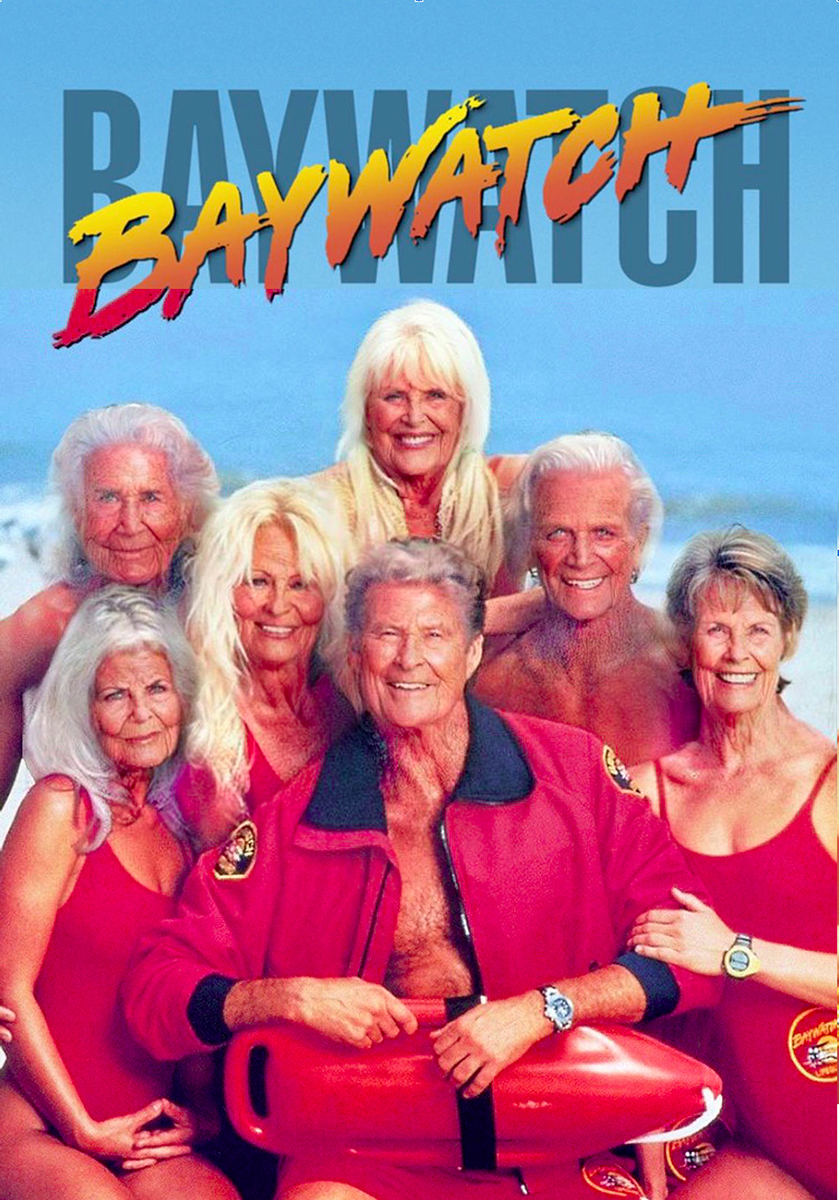

Viewers in the 1980s zapped between altered faces: from fashion shows to the latest Baywatch season, from rap videos with tans, thongs, and full-body waxing against blue pools to political TV shows—interspersed with detergent and shampoo ads—all featuring smiling, often laughing, faces.

Baywatch in 2023, with Pamela Anderson and lifeguards, all wearing their radiant smiles—aged with AI assistance. Gwenola Wagon.

As cosmetic surgery becomes more accessible, viewers can reshape their own appearance to mirror their idols. Just a few seconds of Claudia Schiffer on a catwalk are enough to make one want to copy her lips, teeth, and slim figure.

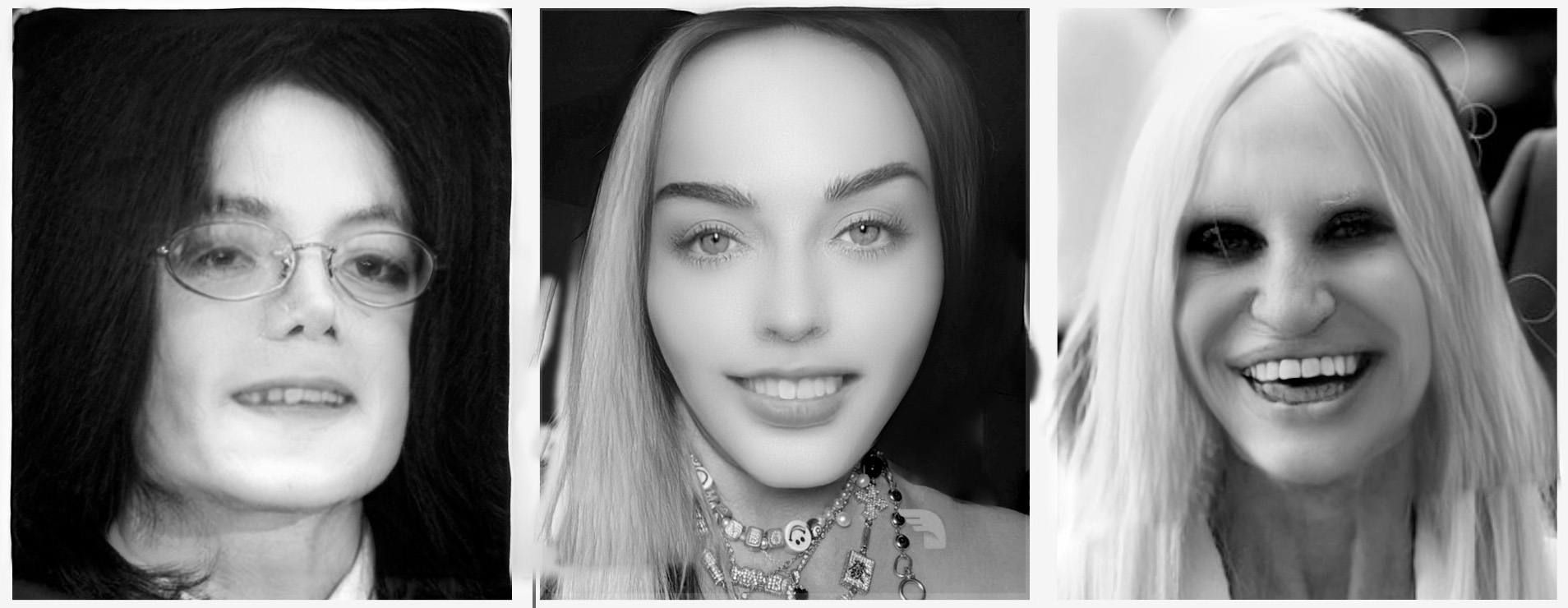

After 2016, the term deep fake emerges to describe techniques allowing near-instant facial expression manipulation in video. How can we not see these hyperfakes as an extension of the decades-long transformation of bodies and faces in media? The scandal around deep fakes arises in a context where showbiz figures (Paris Hilton, Kim Kardashian, Madonna, Donatella Versace, Jennifer Aniston, Meg Ryan, Kim Novak, Melanie Griffith, Courtney Love, Isabelle Adjani, Michael Jackson, Jennifer Lopez, Mickey Rourke, Sylvester Stallone…) embody the blur between authenticity and falsification, striving to look like idealized versions of themselves. These figures no longer seem human—but embalmed icons of their own perfection.

Portraits of Michael Jackson, Madonna, and Donatella Versace after surgery and automatic AI retouching.

In the 2000s, new substances supplement the scalpel to reshape bodies. Many labs offer Botox and hyaluronic acid injections to relax facial muscles, adjust volume, add cheekbones, masculinize jaws, fill hollow cheeks, correct under-eye circles, plump lips, or round out buttocks.

The smile becomes disconnected from wrinkles and other facial expressions. In other words, the model smiles with a smooth, relaxed face, altering actors’ expressions—and thus the portrayal of emotions in media.

Michael Salzhauer, aka Dr. Miami, and a patient. Drawing by Gwenola Wagon after the documentary by Olivier Lemaire, Instagram: Vanity Fair, 2022.

The American celebrity Michael Salzhauer, aka Dr. Miami, runs a plastic surgery practice in Bay Harbor Islands, Florida. In an interview, he explains how Instagram catapulted his practice to reach a global audience:

"These days, patients come in with photos of Instagram celebrities. And they want to look like them. There is such a demand for cosmetic surgery in the world that it exceeds supply. During the coronavirus, no one could do anything—we only went out to get tested. A lot of people asked me: why can’t we do Botox injections without getting out of the car? So we did it! And it was great! Without social media, how could I have done something like that?" 39

The Smile Dictatorship

Since the advent of apps like FaceApp, TikTok, and Snapchat, both faces and landscapes have become malleable. Image post-production is now within everyone’s reach: it’s easy to artificially make people smile in photos, turn them into movie stars, saturate colors, and boost contrasts to give settings a spectacular appearance—enhancing the appeal of iridescent lights, northern lights, sunsets, and azure skies over beaches and mountains.

Snapchat launched Time Machine, and TikTok released Bold Glamour. These aren’t just virtual surgeries, but also drugs, sparking a form of addiction to representations.

As a result, we become used to juggling divergent realities to escape the unhealthy dissatisfaction with our own appearance. To smooth. To sweeten. To beautify. To rejuvenate. To age. To hybridize. To be as attractive as possible. To alter ourselves to the point of resembling no one at all, embodying no existing being—neither real nor virtual—transformed by real-time filters into chimeras.

This led Australian reality TV star Abbie Chatfield to say about TikTok’s Bold Glamour filter:

“If I weren’t an adult, honestly, this thing would rot my brain.” 40

The obsession with transforming one’s appearance via apps and filters would create new forms of dysmorphia—between the “real” face and the “fantasized” face.

In this dissociative context, the famous quote from designer Victor Papanek, “Real needs for a real world” 41, would become:

“Virtual needs for a virtual world.”

A smile from Tom Cruise.

Background Happiness as Palliative Care

The landscape is transformed into a backdrop as if by magic.

Faces, bodies, and backgrounds are reconstructed, smoothed in real-time like the actors and sets of Hollywood films, magazines, video games, or manga, to increasingly match our desires.

Images bend to a sublimated—or even hallucinated—idea of reality.

The exceptional becomes commonplace.

And this does not leave our relationships with others or the environment unscathed.

The terraforming of reality obeys the logic of the image.

Screenshot from Gwenola Wagon's film, Chronicles of the Black Sun, 2023.

Happiness is distributed through modified image representations.

The world is treated like a green screen.

Stock images, ambient music, air conditioning, cosmetic surgery, AI-based retouching… all aim at a kind of conformity, neutrality (visual, auditory, thermal) to create a smooth, homogeneous, predictable, surprise-free, comfortable environment.

Happiness as a median point.

Like air conditioning and Muzak, stock images are never too cold or too hot. No matter what they depict, their overall tone is neutral. Air conditioning ensures physical comfort. Muzak and stock images ensure mental comfort. The mind naturally flows into familiar sounds and images, never jarred, receiving instead the melody and vision of peaceful happiness.

Screenshot from Gwenola Wagon's film, Chronicles of the Black Sun, 2023.

These background technologies are not trying to manipulate us, sell us products, change our ideology, or make us vote for someone. They distill a living environment—a light, normal, fresh, invisible, and omnipresent happiness in which we are immersed. They give color to our surroundings. Perfectly compatible with standardized architecture and the creation of a neutral, air-conditioned atmosphere found in international airports 42, malls, and offices.

A background bath.

As explained in Mathieu Stern's tutorial "7 TIPS that Will Make You SMILE Naturally on every PHOTO", available on YouTube, one should no longer say “Say cheese” to make people smile in photos. That word, in fact, triggers a forced, “non-Duchenne” smile.

He suggests replacing it with the command “Say Money!”, which provokes a genuine smile.

Indeed, one can observe the huge number of smiling people under showers of money in image banks.

Performance La photo :) toute seule© Photos from Université Paris 8 / (top and bottom) Audiovisual Creation Service – Patrick Masclaux @pinouck

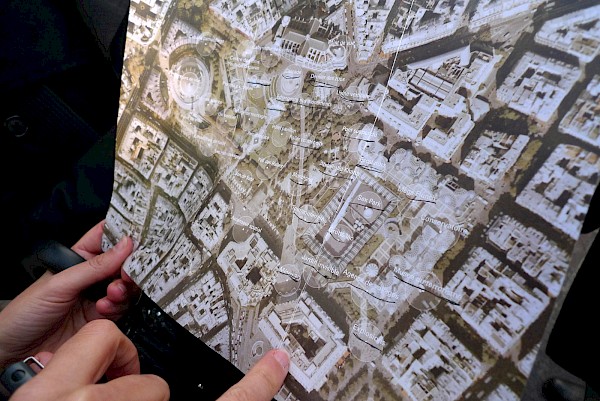

Epilogue – Traveling through Wallpaper Backgrounds

A typical wallpaper image. Source: Pexels

This image of a paradise island represents a contemporary ideal—the quintessence of what Kodak sought to produce in its advertisements: a condensation of moments of escape, travel, vacation, prosperity, calm, beauty, and pleasure...

This landscape is a filtered version of itself. It's often used as a wallpaper background. Remote workers use it in video calls to convince themselves they’re not stuck in a grim office or hiding in their studio apartment closet. Cut out against a green screen, they virtually transport themselves to stereotypical tropical islands.

In recent years, following the pandemic, many white-collar workers have gone into exile. Digital nomads, they flee cities and suburbs for Airbnbs overlooking paradise coastal landscapes. They move into the image of their desktop wallpaper.

Their wallpaper photo becomes the background of their life.

The fantasized wallpaper becomes the real-life setting for the remote worker.A remote worker working anytime, anywhere, whether in Bermuda or the Canary Islands.

(But to conceal their dream destination, remote workers now overlay themselves in real time in front of virtual office images.)

Bibliographie

Jacques Amblard, « Les musiques obligatoires », version corrigée en 2009, dans le cadre du colloque universitaire Musique et politique : les pouvoirs du son, 2021.

Charles Baudouin, Suggestion And Autosuggestion, New York, Dodd, Mead and Company, 1921

Charles Baudouin, Frank Abauzit et al., Emile Coué. Sa méthode, son esprit, son influence, Paris, Librairie Félix Alcan, 1928.

Bruce Bégout, La Découverte du quotidien, Paris, Allia, 2005.

Estelle Blaschke, Banking on Images: The Bettmann Archive and Corbis, Leipzig, Spector Books, 2016.

Edgar Cabanas, Eva Illouz, Happycratie. Comment l’industrie du bonheur a pris le contrôle de nos vies, Paris, Premier parallèle, 2018.

Lionel Chapouteau, Libres d’obéir. Le Management, du nazisme à aujourd’hui, Paris, Gallimard, 2020.

Stéphane Degoutin, Gwenola Wagon, Psychanalyse de l’aéroport international, Cognac, 369 éditions, 2019.

Sylvain Desmille, My American (Way of) Life, (film documentaire), 2015.

André Gazut, Une si douce musique (film documentaire), RTS, 1978.

Rinny Gremaud, Un Monde en toc, Paris, Seuil, 2018.

André Gunthert, « Un sourire de classe. Le portrait photographique et la culture de l’expressivité », Transbordeur. Photographie, histoire, société, n° 6, février 2022.

André Gunthert, Pourquoi sourit-on en photographie ? Lyon, Deux-Cent-Cinq, 2023.

Anthony Haden-Guest, The Paradise Program: Travels Through Muzak, Hilton, Coca-Cola, Texaco, Walt Disney, and Other World Empires, New York, William Morrow & Company, 1973.

Rob Horning, « The preponderance of the object », Internal exile, 25 August 2023, robhorning.substack.com

Christina Kotchemidova, « Why We Say “Cheese”: Producing the Smile in Snapshot Photography », in Critical Studies in Media Communication, vol. 22, n° 1, March 2005.

Jenka, « AI and the American Smile. How AI misrepresents culture through a facial expression », medium.com, 27 mars 2023.

Joseph Lanz (sic), « Muzak and the Global Nursing Home », Exit, n° 2, 1985.

Joseph Lanza, Elevator Music: A Surreal History of Muzak, Easy-Listening, and Other Moodsong, New York, St Martins Pr, 1994.

Olivier Lemaire, Instagram : la foire aux vanités, (film documentaire), 2022.

Roland Meyer, compte X

Edgar Morin, Les Stars, Paris, Le Seuil, 1972 (1957).

Sydney Ohana, Histoire de la chirurgie esthétique de l’Antiquité à nos jours, Paris, Flammarion, 2006.

Rémy Pawin, « Le bien-être dans les sciences sociales : naissance et développement d’un champ de recherches », L’Année sociologique, vol. 64, n° 2.

Victor Papanek, Design pour un monde réel, Dijon, Presses du réel, 2021 (1971).

Pierre-Pascal Rossi et André Gazut, Une si douce musique (film), RTS, 1978.

Beryl Satter, Each Mind a Kingdom. American Women, Sexual Purity, and the New Thought Movement, 1875-1920, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1999.

Notes

-

Christina Kotchemidova, « Why We Say “Cheese”: Producing the Smile in Snapshot Photography », in Critical Studies in Media Communication, vol. 22, n° 1, March 2005, p. 2-25. Voir aussi André Gunthert, « Un sourire de classe. Le portrait photographique et la culture de l’expressivité », Transbordeur. Photographie, histoire, société, n° 6, février 2022, p. 136-149 et André Gunthert, Pourquoi sourit-on en photographie ?, éd Deux-Cent-Cinq, 2023. Voir aussi l’ouvrage d’Angus Trumble sur l’apparition du sourire dans l’histoire de l’art, A Brief History of the Smile, Basic Books, 2004. ↩

-

« Strictly speaking, there’s no such thing as invention, you know. It’s just magnifying what already exists. », Peter Weir (réalisation), Paul Schrader (scénario), The Mosquito Coast, 1986. Toutes les traductions sont des auteurs, sauf mention contraire. ↩

-

« Le secret du bonheur », L’intransigeant du 6 juillet 1926, publié à la mort de Coué. Frank Abauzit, Charles Baudouin, le docteur Bernoulli et al., Émile Coué : sa méthode, son esprit, son influence, Paris, librairie Félix Alcan, 1928. ↩

-

Émile Coué est également l’un des découvreurs de l’effet placebo. ↩

-

Frank Abauzit, Charles Baudouin, le docteur Bernoulli et al., Émile Coué : sa méthode, son esprit, son influence, Paris, librairie Félix Alcan, 1928, p. 47 et p. 52. ↩

-

L’une des deux écoles, avec celle de la Salpêtrière, ayant contribué au développement de l’hypnose thérapeutique au XIXe siècle. Retour au texte ↩

-

Emma Curtis Hopkins (1849-1925) est la fondatrice de la New Thought ; Mary Baker Eddy (1821‑1910), qui fonda la Christian Science et Phineas Parkhurst Quimby (1802-1866) sont considérés comme les précurseurs du mouvement. Voir la biographie de Mary Baker Eddy (ainsi que de Franz-Anton Mesmer et Sigmund Freud) dans Stefan Zweig, La guérison par l’esprit, 1931 ; Charles S. Braden, Spirits in Rebellion : The Rise and Development of New Thought, Southern Methodist Univ Press, 1963 ; Beryl Satter, Each mind a kingdom : American women, sexual purity, and the New Thought movement, 1875-1920, University of California Press, 2001. ↩

-

Pierre Janet, dans Frank Abauzit, Charles Baudouin, le docteur Bernoulli et al., ibid., p. 93‑94. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Beryl Satter, Each Mind a Kingdom. American Women, Sexual Purity, and the New Thought Movement, 1875-1920, University of California Press, 1999, p. 6 (notre traduction). ↩

-

Que l’on traduit généralement en français – faute de mieux – par « développement personnel ». ↩

-

Auteur de How to Win Friends & Influence People, New York, Simon & Schuster, 1936. ↩

-

Auteur de Think and Grow Rich, Meriden, CT, The Ralston Society, 1937. ↩

-

Auteur de The Power of Positive Thinking, Hoboken, NJ, Prentice Hall, 1952. ↩

-

Auteur de The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, New York, Free Press, 1989. ↩

-

Autrice de Mindset : The New Psychology of Success, New York, Random House, 2006. ↩

-

Rémy Pawin, Le bien-être dans les sciences sociales : naissance et développement d’un champ de recherches, L’Année sociologique, vol. 64, n° 2, p. 273-294. ↩ ↩

-

George French, Twentieth century advertising, New York, Van Nostrand, 1926, cité dans Christina Kotchemidova, op. cit. ↩

-

Christina Kotchemidova, ibid. ↩

-

Marie-Charlotte Calafat et Frédérique Deschamps, Roman-photo, Paris : Textuel ; Marseille : Mucem, 2017. ↩

-

Sylvain Desmille, My American (Way of) Life, film documentaire, 2015. ↩

-

Aldous Huxley, Brave New World, Londres, Chatto & Windus, 1932. ↩

-

Créée en 1934, l’entreprise Muzak, a fait faillite en 2010 et a été rachetée par Mood Media en 2011. ↩

-

Titres cités dans Anthony Haden-Guest, The Paradise Program: Travels Through Muzak, Hilton, Coca-Cola, Texaco, Walt Disney, and Other World Empires, New York, William Morrow & Company, 1973. ↩

-

Anthony Haden-Guest, op. cit., p. 18. « Boring work is made less boring by boring music » fut du reste un véritable slogan de Muzak, lancé sous la direction d’Umberto V. Muscio mais vite abandonné. ↩

-

Joseph Lanza, Elevator Music. A Surreal History of Muzak, Easy-Listening, and Other Moodsong, New York, Picador, 1994, p. 3. ↩

-

Le terme « photographies de stock » désigne des images prises sans commande spécifique et proposées sous licence à des clients tels que des éditeurs, des publicitaires et des entreprises, via des banques d’images. Cette commercialisation a connu une expansion par le biais de « micro-stocks » qui fonctionnent selon un modèle de rétribution « ubérisé » de type économie de plateforme. Ces images conçues pour répondre à une multitude d’usages, recourent souvent à des figures génériques et archétypales. Pour une histoire approfondie des banques d’images, voir le livre d’Estelle Blaschke, Banking on Images : The Bettmann Archive and Corbis, publié en 2016 chez Spector Books. ↩

-

Voir Stéphane Degoutin et Gwenola Wagon, « Le blanchiment des images », AOC, 6 avril 2022. L’article complet est disponible sur notre site d-w.fr, page « Projets / Le blanchiment des images ». ↩

-

Rob Sylvan, Taking Stock: Make money in microstock creating photos that sell, Berkeley, Peachpit Press, 2011, p. 40. ↩

-

Les sites distinguent d’ailleurs les photos d’événements réels sous l’appellation de « contenu éditorial », et celui-ci ne peut pas être utilisé pour des usages commerciaux. ↩

-

Rob Horning, « The preponderance of the object », Internal exile, 25 August 2023, robhorning.substack.com ↩

-

Jenka, « AI and the American Smile. How AI misrepresents culture through a facial expression », medium.com, 27 mars 2023. ↩

-

Rémy Pawin, Le bien-être dans les sciences sociales : naissance et développement d’un champ de recherches, L’Année sociologique, vol. 24, n°2, p. 273-294. ↩

-

Cité sans indication de source dans Sydney Ohana, Histoire de la chirurgie esthétique de l’Antiquité à nos jours, Paris, Flammarion, 2006. ↩

-

Edgar Morin, Les Stars, Paris, Le Seuil, 1972 (1957). ↩

-

On la pratiquait déjà – par exemple – dans l’Égypte et la Rome antiques, en Inde au VIIIe siècle, etc. ↩

-

Pour compléter le premier effectué aux États-Unis. ↩

-

Sydney Ohana, op. cit. ↩

-

Documentaire d’Olivier Lemaire, Instagram : la foire aux vanités, 2022. ↩

-

« If I wasn’t a full grown adult this would rot my brain tbh, » Photo : TikTok/abbiechatfield ↩

-

Victor Papanek, Design pour un monde réel, Dijon, Presses du réel, 2021 (1971). ↩

-

Stéphane Degoutin et Gwenola Wagon, Psychanalyse de l’aéroport international, Cognac, 369 éditions, 2019. ↩